Kim Hankyul, a decade of crafting sounds

Swish, swoosh, iiik, screech, thud, clank, click. If you close your eyes in any of Kim Hankyul’s kinetic installations you are transported to another soundscape, to another world. His work merges the handmade with the Foley artist’s attentive ear; he is drawn towards the darker recesses of humanity; and he reveals a concern for those who have been othered by the dominant social order.

Crafting sounds

A Foley artist is someone who creates sound effects for films. They are named after Jack Foley (1891–1967) who developed a live method for matching sound effects with the visuals of a film during post-production. The techniques came from radio plays and moved into the film industry with the dawn of “the talkies”. Well-known examples include using two coconut-halves to create the sound of horses’ hooves, squeezing cellophane to create the impression of a crackling fire, and shaking large metal plates, known as “thunder sheets” to conjure up a storm. With the advent of more sophisticated microphones for recording ambient sounds and vast digital special effects libraries, the art of the “live” studio foley artist disappearing. It is, therefore, with a certain nostalgia that I watch Hankyul go to extreme – analogue – lengths to create the soundscapes for his new installation, Shore.

Hankyul says that his initial interest in Foley artists’ work was piqued by mishearing. Initially it was a broken motor, which he thought was a friend snoring. It is over ten years since he moved from South Korea for Norway and, as anyone who has relocated to a new country knows, your ignorance of the language heightens your perception of its sounds. With this enhanced attention, Hankyul is an artist who moves through the world with a keen interest in not just how things sound, but how they are made to make that sound. The visual expressions of his installation are characterised by an honesty: the things that generate sounds, the microphones that enhance them, the cables that transmit them, and the speakers that broadcast them are all visible. They often double as some kind of form giver: cables become the outline of a head, drum sticks appear as limbs, screens become makeshift eyes.

Bearbeide

The number of words in the English language vastly outnumbers Norwegian ones. Nonetheless, there is a Norwegian word that describes Hankyul’s process better than any English equivalent. The word is “bearbeide”, used to describe both working on and working through. It has at least four different uses in Norwegian and contains subtleties that the English words “work” and “process” fail to capture.[1] It can mean to work on something for a long time and/or thoroughly, and it can refer to a technological process in which raw materials become refined products. It also means to give form to an artwork or to adapt a play. Finally, it can also refer to intense persuasion or influence. “Bearbeide” has tactile connotations as well as emotional and intellectual ones. It implies working with something over time to give it form. You can “bearbeide” (work) the land, but also “bearbeide” (process) impressions, trauma and pain. Hankyul is drawn to images and imaginaries of war, suffering and fugitivity. A reference for his new work for the SOLO OSLO series at MUNCH was the book The Drowned and the Saved by Holocaust survivor Primo Levi (1919–1987). It was the last book he published in 1986, and consists of eight essays where he analyses his experiences at the Nazi concentration camp Auschwitz. Refusing simple binaries between good and evil, victim and perpetrator, his work thematises unimaginable suffering and survival, while attempting to make sense of the human condition and morality under and within oppressive systems of totalitarian control. The Drowned and the Saved and Levi’s body of work as a whole is an attempt to “bearbeide” the horrors of humanity that the Holocaust revealed.

Kim Hankyul, The Temple of the Golden Pavilion, 2019. Photo: Jane Sverdrupsen

A decade of sound work

For over 10 years Hankyul has made kinetic sculptures using light, sound and movement. They have beguiled and bewildered viewers since the beginning. An early blogpost on an exhibition he did in Seoul in 2016 referred to the works’ “strangeness” that created “a sensation never before experienced”. [2] At his MA degree show in 2019, which takes the form of a group show at Bergen Kunsthall, reviewer Susanne Christensen described his work The Temple of the Golden Pavillion as a “showstopper” with skeletal building structure, a “hell machine” that intermittently emitted the smacking sounds of a whip and rumbling noises.[3] Gabrielle de la Puente, from The White Pube described the same work as following: “this agitated sound would fill the gallery and I honestly don’t know how else to describe the effect of this except to say it was like the house had a fetish? Like it was shivering, burnt, hurting itself and noisy in its breakdown.”[4] Later works, like The Tempest (Stormen) (2021) would make literal use of the Foley artist’s “thunder plates” to create the titular storm, which was shown both at Bergen’s Ekkofestival (2020) and the Høstutstillingen (the annual autumn exhibition) in Oslo (2021) where it was awarded the Kistefos Prize. Throughout, reviewers’ associations were those of ominousness with a hint of fascination.[5]

Kim Hankyul, The Tempest (Stormen), 2021. Photo: Dale Rothenberg

AV Buddha was a work that won Kim Hankyul the Sparebankstiftelsen DNB's grant when it went on display at Oslo Kunstforening in November 2022 together with two other nominated artists. The jury wrote:

An extraordinary technical achievement, the work is equally complex conceptually, sonically, and aesthetically. At once moving and disquieting, it transforms neglected stories of the Korean war into an uncanny mechanical and musical symphony, reflecting at the same time on the cacophony of contemporary acceleration online media culture. While dealing with the unresolved history of Korea, AV Buddha also points to the mediated character of modern conflicts more widely. It is a deeply affecting anti-monument to those lives which continue to be marginalized in collective memory.[6]

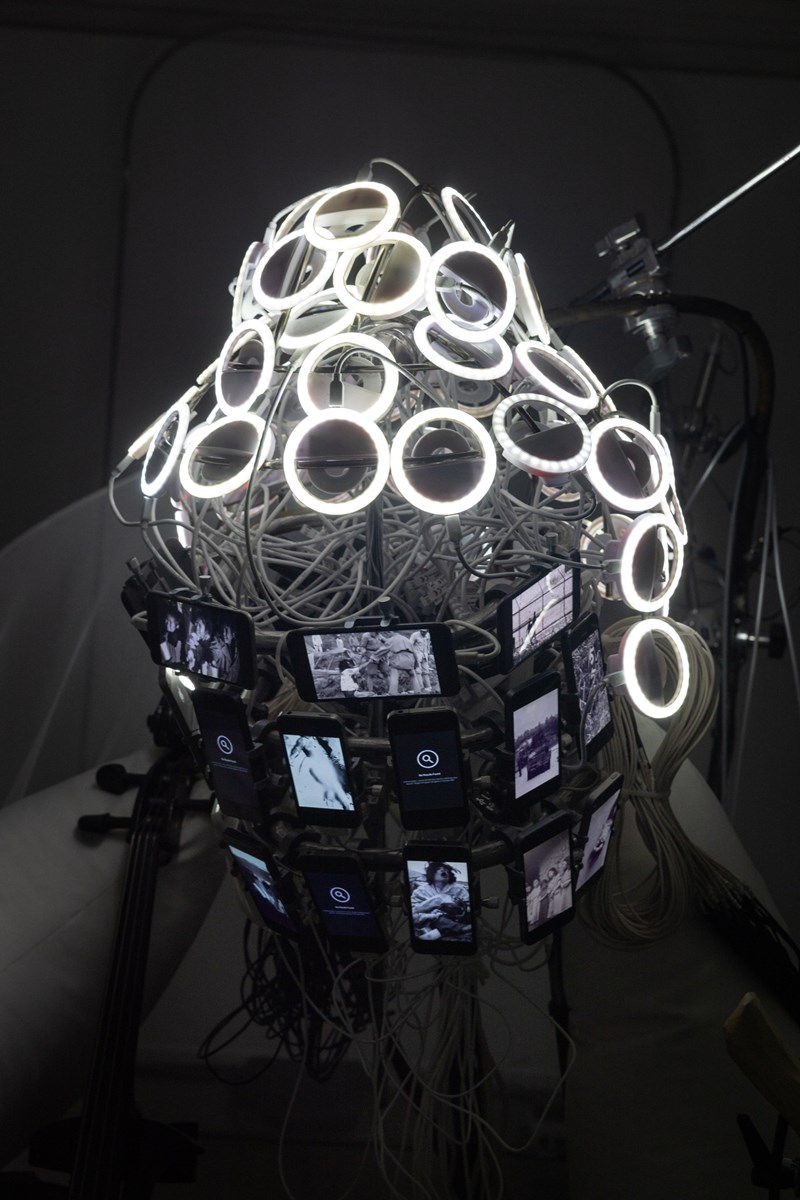

Kim Hankyul, AV Buddha, 2022, Oslo Kunstforening. Photo: Julie Hrnčířová.

The work was later acquired by the Astrup Fearnley museum, marking Hankyul’s first museum acquisition. The title of AV Buddha was a clear reference to Nam June Paik’s TV Buddha (1974), which shows a Buddha statue watching his own image on a television set, captured by CCTV. Hankyul’s installation was loosely in the shape of a somewhat deformed Buddha with metal rods, elongated soft cushions and wooden bones making up the skeleton and body, while the head was composed of round lights, a nest of cables and several iPhone screens inserted into a circular structure. On the screens, black and white found footage from East Asian contexts, mainly of people who were unable to cross militarized borders. Some of the screens displayed a generic representation of a magnifying glass, indicating that an image search had showed up nothing. Hankyul later told me that these were the result of him typing in the search terms “homeless fugitive” and “transgender border crossing”. These identities did not exist in the search engine’s image bank and pointed to the invalidation of lives those without a fixed abode or without a stable gender identity. For Hankyul this had become evident as people sought to flee the Russian invasion of the Ukraine that same year when he was completing AV Buddha. War has a way of entrenching binary categorisations of “citizen/enemy”, “soldier/civilian”, “useful/expendable”. In The Drowned and the Saved, Levi criticises such binaries, instead putting forward the notion of a “grey zone” that can harbour nuance and hold conflicting notions at once.

Kim Hankyul, AV Buddha (2022), Oslo Kunstforening. Photo: Julie Hrnčířová.

The soundscape of AV Buddha was made up of a whispered voice-over, the hammer of metal on metal, the enhanced bubbling of water put in motion by a fan, the clanging of several wooden pieces on a string hitting the floor, the delicate tones of a DIY cello being played by a mechanical, wooden arm. The flashing lights and harsh sounds underlined the violence of the imagery. The noise was repelling, yet the mechanics of the installation drew one closer in, moving the gaze from each source of sound to another. As a whole, it held a kind of morbid fascination, a cyborgian monster gurgling, banging and twitching.

While AV Buddha was on display at Oslo Kunstforening, Hankyul also opened a solo exhibition Bildungsroman at Nitja Center for Contemporary Art at Lillestrøm, just outside Oslo. The title refers to the German term for a coming-of-age novel, which will traditionally follow a young person on their journey to maturity. Bildungsroman at Nitja had a strong instrumental component as a set of traditional cymbals placed outside the main installation, joined the more homemade drums and other percussive elements. Already at this “prelude” stage of the cymbals, visitors could read a leather tag embossed with a quotation from Oscar Wilde in ornate handwriting. Smaller leather tags made up two windchime-like hanging sculptures with key phrases from seminal books of queer literature and pop culture: from Sarrasine (1830) by Honoré de Balzac to Drag (2019) by Simon Doonan. Like AV Buddha, the main figure of Bildungsroman could be found in the centre of the space, its limbs similarly made up of flaccid pink pillows, which intermittently filled with air. Individual titles such as “Breathing and snoring and hiccupping, belching and flatulating and screaming and hungry machine” gave the construction sentient, if not human, qualities.

Kim Hankyul, Bildungsroman, 2023. Photo: Kunstdok/Tor S. Ulstein

The plush carpet and velvety valances that partially clad the lower sections of the walls created a more hushed sonic landscape than the sharp noises amplified by the wooden floors at Oslo Kunstforening. In Bildungsroman, the dulcet tones of dripping water joined the gentle squeaks of air entering and escaping the textile shapes, creating the impression of a rich jungle soundscape, in stark contrast to the plain sandy, pink and burgundy colours that visually dominated the space. This was a soft alternative forest with dark mauve flowers made of scrunchies and an undergrowth of reclaimed dark wood with extension cables snaking across the carpeted floor like etiolated vines. Whereas the found footage in AV Buddha offered narrative clues, Bildungsroman relied on its snippets of literature to guide visitors towards a queer reading of the work. Quotes like “I did not want to pass as a woman. I wanted to pass as a monster” from H.P Lovecraft and “all monsters are queers” from Derek McCormack made the connection between the monstrous construction in the middle of the space and queerness and monstrosity clear. Small, fleshy sculptures, referred to as being part of a “colony”, lay strewn about the floor like little mutants of their mother figure with toes and nipples. It is interesting to note in reviews of the exhibition how appreciated these pink ceramic sculptures were.[7] Perhaps their relative size provided a favourable juxtaposition with the loud, belching, farting creature in the middle of the space. Or perhaps their recognisably human attributes even in their foetal state garnered sympathy and the imaginative leap to make them whole.

Kim Hankyul, Bildungsroman, 2023. Photo: Kunstdok/Tor S. Ulstein

In the overlit gallery space of Kunstnerforbundet in Oslo a year later the atmosphere was very different to the soft, subdued spaces at Nitja. Forest_Sound_Motor_Machine.mov (2024) gave the impression of a bright operating theatre, albeit with the presence of a green screen which alluded to the film industry. Here, the voice-over and the visual material displayed on small Iphones and on large, curved LED screens combined to convey a description of a green forest being traversed by soldiers. A background track of slightly distorted electronic music was joined by the rattling of metal chains, the tap of plastic on wood and the whirring of small fans. Sheets of silicone rags were draped over metal stands, like discarded skin. Parts of a wooden carcass resembling that of a dinosaur with a loose spine, bones and giant teeth creaked and shook. Inspired by the story of a former soldier’s processing (bearbeiding) of his memories of war through interviews and simulation.

Kim Hankyul, Forest_Sound_Motor_Machine.mov, 2024. Photo: Jon Gorospe/jg.videolab

Shore at MUNCH

Hankyul describes Shore as a soundscape of an ocean. Oceans have been used as escape routes or as a place for people who cannot find their “proper” identity on land. As he is speaking of this in the studio in Oslo, I cannot shake the image of him as a child in the port city of Busan, walking along the seashore after school. There is a reason that oceans hold such imaginary potential for so many artists, writers, adventurers. They beckon restless souls to traverse them in search of an alternative future. For some, the ocean itself becomes a source of sustenance, a way of making a living through gathering and harvesting. For others, it holds dread, an awareness of the lives lost through drowning. The richness in oceanic imaginaries in cultural production is telling: from the ancient Greek tales of Atlantis and its renewed utopian framing in the 16th century via Jules Verne submarine stories in the 19th century to the more dystopian science fiction of the 20th century to contemporary film productions like Avatar or Black Panther. Over the course of this project for MUNCH, Hankyul has been reading North Korean science fiction, for example Shin Seung-gu, and says that it is interesting to note that in his books, the ocean is a utopian place, characterised by an abundance of food and flying fish, in contrast with the more dystopian tendencies of North-Atlantic science fiction.

Like many of his earlier works, Shore features a low voiceover. These are based on interviews Hankyul conducted over the course of 2025. The accounts fall into three categories that all operate in some way under water: those who have used to the ocean to escape in the form of a North Korean defector; a haenyeo (“ocean women”) community on the South Korean Geoje Island, who made the sea their source of survival after being displaced following the Korean and Vietnam wars; and members of a private divers’ association, who are the first responders to aquatic disasters in South Korea. Their testimonies are provided in the form of Korean voice-overs that join the rest of the sound installation, finding their way between the ebb and flow of the crashing waves. Subtitles are provided in Norwegian, English and Korean via holograms, whose whirring fans join the rich soundscape.

The oceanic soundscape is created through skeletal wooden bones running over computer keys, mounted with microphones and broadcast through surrounding speakers. Pneumatic motors thud and clank, drawing associations with an active port, where chains hit the bows of ships and forklift trucks fill containers with cargo. The core of Shore as an installation is suspended from the eight-meter-high ceiling in in the characteristic gallery spaces on Level 10 at MUNCH, in the building’s “kink”. Three makeshift cages hang at different height, reflecting the depth of the ocean that each narrative is concerned with. The soft carpet and curvature of the floor create the sensation of walking on the seabed. Looking up, visitors get the impression of finding themselves just below the surface of the water, which gently refracts rays of sunshine. The installation is bathed in a blue hue with greater attention paid to the lighting design than any of Hankyul’s previous works. The challenge of suspending such a technologically complex installation from the ceiling is another departure for Hankyul. However, there are elements of earlier works evident in Shore including the soft furnishings from Bildungsroman, the wooden bones, string instruments and images of war from AV Buddha, and the draped silicone sheets from Forest_Sound_Motor_Machine.mov. These silicone sheets feel like melted skin in their materiality, but with the oceanic connotations of the work, they also resemble dilapidated ship’s sails. Clinging to the bare bones, moving unsteadily within each cage, my thoughts are drawn to starvation, threadbare clothing and to the carcasses of fish and other sea creatures, easily confused with sun-bleached driftwood, washed up on the shore. To reassembled these might result in a creature not unlike Hankyul’s, a proto-Frankenstein of the oceanic depths.

What strikes me about Hankyul’s work having surveyed the last decade of his practice is how they engender imaginative leaps on the part of their viewers, how they ascribe narrative to semi-abstract mechanical forms. In The crisis of narration (2024), philosopher Byung-Chul Han points out how digital technologies and social media have brought on a shift from narration to information, from storytelling to “storyselling”.[8] From a community formed around shared narratives, digital screens have separated people as individual, lonely consumers. What art can do, is to slow down consumption of visual information by celebrating complexity and rejecting easy conclusions. It trains our imaginations and ability to create narrative by refusing to serve up a finished story. Citing Walter Benjamin’s essay The Storyteller (1936), Han underlines the fact that “the art of storytelling demands that information be withheld.”[9] It is in its withholding that Hankyul’s narrativity works so well. All (good) artworks have an ineffable quality, something that evades capture by language. Amongst the swish, swoosh, iiik, screech, thud, clank, click, the motors and the limp materials made to move, a profound sense of meaning emerges in Kim Hankyul’s work, touching the deep recesses of the soul.

End notes

[1] https://naob.no/ordbok/bearbeide

[2] Jungwook Kim, “An awkward consolation from unpainted materials”, Seoul Foundation for Art and Culture, March 11, 2016. http://m.blog.naver.com/i_sfac/220652335396

[3] https://kunstkritikk.no/elektrisk-af-ideer/

[4]Gabrielle de la Puente, https://thewhitepube.co.uk/art-reviews/with-eyes-closed-call-me/

[5] See, for example, Nicholas Norton, “Med et brak, kløyves himmelhvelvingen”, Billedkunst no.3, 2021, pp. 224–225. https://www.norskebilledkunstnere.no/billedkunst/aktuelt/med-et-brak-kloyves-himmelhvelvingen/ or Oda Bahr in Periskop 12.11.2021 https://periskop.no/hostutstillingen-2021-en-lavmaelt-apokalypse/?fbclid=IwAR37e_AfPWxdKcvN_Y15zVp20hOI2oDsonP6FA3Elegn7M_gA3PiKIFWZWg

[6] https://www.oslokunstforening.no/en/exhibitions/sparebankstiftelsen-dnbs-stipendutstilling-2022

[7] See for example, Arve Rød, “Dr. Frankenstein på Lillestrøm”, Kunstavisen, 26 January 2023.

https://kunstavisen.no/artikkel/2023/dr-frankenstein-pa-lillestrom or

Mona Pahle Bjerke, “En dannelsesreise - utstillingen traff meg som et knyttneveslag i magen.”, NRK, 17 January 2023.

https://www.nrk.no/anmeldelser/anmeldelse_-_bildungsroman_-av-kim-hankyul-1.16258537

[8] Byung-Chul Han, The crisis of narration, trans. Daniel Steuer (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2024), Preface, p. X.

[9] Han, p. 2.